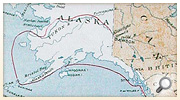

By the end of July 1897, prospectors started to flood in to Dyea and Skagway in a steady stream. Hal Hoffman, in the Official Guide to the Klondike Country, observed: “the rush still keeps up and the end is not in sight... The end is in New York, and Chicago, and San Francisco.”

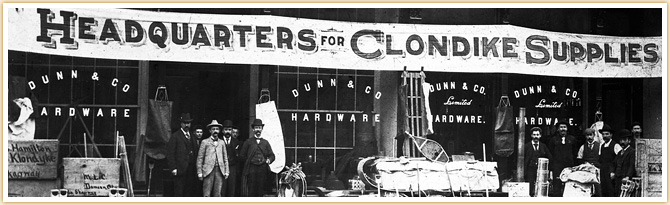

Anyone heading into the Yukon had to have the required “ton of goods” — a year’s supply of food (about 1000 pounds, at three lbs. per day) plus another 1000 lbs. of equipment. They had to relay this outfit in stages, caching each load and returning for another.

Stores in Vancouver, Victoria and other cities competed to supply miners’ outfits.

Yukon Archives, Bill Roozeboom collection, #6303

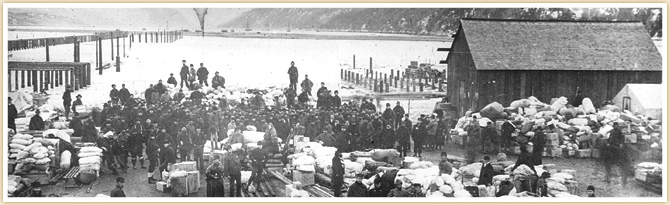

At Dyea, goods and passengers were off-loaded at low tide; many supplies were spoiled or carried away by the rising tide before their owners could claim them. Healy and Wilson’s pack train ran every day from Dyea to Sheep Camp, each horse carrying 90 kilos, and First Nations packers and non-native packers also worked steadily, but no one could keep up with the demand.

It is impossible to give one an idea of the slowness with which things are moving. It takes a day to go four or five miles and back; it takes a dollar to do what ten cents would do at home.

TAPPAN ADNEY, DYEA, AUGUST 1897, THE KLONDIKE STAMPEDE

In Skagway, the White Pass trail turned into a quagmire in late August from heavy traffic and 11 days of rain, and had to be closed for repairs for four days. And still the people poured in.

Studio portrait of a First Nations packer, ca. 1898. For countless years the coastal Tlingit controlled the routes to the interior. The Raven clan of the village of Chilkoot, south of Dyea, had a monopoly on the Chilkoot Pass until the 1880s; they subsequently allowed miners to use the route.

Yukon Archives, Eric Hegg fonds, #2561

“It would be difficult for one to imagine the confusion that existed when the tons and tons of boxes and sacks and barrels came ashore...”

R.C. Kirk, 1898, Twelve Months in Klondike

Photo: Yukon Archives, Anton Vogee fonds, #114

After the backbreaking work of carrying their goods over the passes, stampeders faced a 1000-km trip downriver to Dawson. At Lindeman or Bennett they had to fell trees, whipsaw lumber and construct a boat that would withstand the rigours of the Yukon River. All of this was done at a frenzied pace, each person in a panic to get to the gold fields.

“At least one thousand people [are] on the road from Lindeman to Crater, one solid stream of unsatisfied restless humanity.”

L.B. MAY, MARCH 31, 1897

On the river route, stampeders had to navigate the winds of the headwater lakes, the rapids at Miles Canyon and the Thirtymile River, dubbed by the Klondike Nugget “a regular graveyard for boats,” as well as Five Finger Rapids — according to Marvin Sanford Marsh’s diary, a “one-minute ride I will never forget and I never want to take again.” Their long journey finally ended at Dawson, where by June 1897 the few log cabins of the previous year had developed into a chaotic boomtown of 4,000 people.

NWMP

When the Yukon’s first NWMP detachment came north in July 1895 they were the territory’s only official government presence. They collected customs duties, tried to curb the whiskey trade and did what little actual policing was required. During the gold rush they were also inspectors of licences, postmasters and registrars of births and deaths. According to Superintendent Samuel Steele, “every individual in the police force was considered a bureau of information.”

On February 26, 1898, NWMP Inspector Belcher “had the flag hoisted” at the Chilkoot summit and was ready to collect customs. The exact location of the U.S./Canada boundary was in dispute at the time.

Yukon Archives, E.J. Hamacher fonds (Margaret and Rolf Hougen collection), 2002/118 #872

The head of Miles Canyon, ca. 1898. In her diary entry for June 27, 1898, Georgia White writes of having to walk around the canyon since the police wouldn’t allow women or children to “shoot the rapids.”

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections AWC1435

In a letter home to her family dated September 25, 1897, Rebecca Schuldrenfrei wrote of her trip over the Chilkoot Pass: “no living being who has not gone over it can actually imagine or anticipate what it really is.”

Yukon Archives, Winter & Pond fonds, #2293